Game

‘why is a mouse when it spins? because the higher the fewer’

In British English, the phrase appears to have its roots as “when is a mouse if it spins?”. The earliest known appearance, along with its response “the higher it gets the fewer,” can be traced back to The Cornish Telegraph, and Mining, Agricultural, and Commercial Gazette (Penzance, Cornwall, England) on Thursday 29th December 1892.

In British English, the phrase appears to have its roots as “when is a mouse if it spins?”. The earliest known appearance, along with its response “the higher it gets the fewer,” can be traced back to The Cornish Telegraph, and Mining, Agricultural, and Commercial Gazette (Penzance, Cornwall, England) on Thursday 29th December 1892.

THE RIDDLE THAT TURNED MY BRAIN.

The following is taken from a Birmingham paper:—I always thought there was insanity in my family. Now, I know it, and can prove it. The hereditary poison might never have broken out if it hadn’t been for Smoogleslush—l blame. I was all right till that awful evening when he asked me the riddle that cracked my brain. I tried to solve it—until I solve it I am mad—l shall never solve it. My only hope is that the problem I am going to make public will turn other brains too. He took me unawares. He said abruptly, “You’re pretty good at riddles, Flarehead, aren’t you?” “We’ll [sic] I’ve guessed a few,” I said, modestly. “I’m afraid mine’s too simple, too obvious,” said Smoggleslush [sic], “but such as it is, here goes: ‘When is a mouse if it spins?’” “I beg your pardon. ‘When is a mouse if it spins?’ What do you mean?” “That’s the riddle.” “Oh, that’s the riddle. ‘What is a mouse if it spins?’” “No, no, simpler than that. I said, ‘When is a mouse if it spins?’” “You’ve got it wrong, Smoogleslush.” “Not at all. There is no sort of trouble about the question; the cleverness, the clearness comes in with the answer.” “What is the answer?” “It’s a splendid one, make you wonder why you could not see it before. You’ve got the question all right.” “I have.” I said firmly, “‘When is a mouse if it spins?’” “That’s right. Because—the higher it gets the fewer. Ha! ha! ha! ha! See it!” “Yes,” said I. “Plain as a pikestaff, isn’t it?” “Plainer.” Smoogleslush left me. I was left, as it were, face to face, with that awful riddle. If he could see it, why couldn’t I? I repeated it over and over again but every time my brain grew worse. Why couldn’t I see it? My blood curdled as the conviction grew upon me that something had gone wrong with my brain. I decided to go home and try it on my wife. I would pretend I saw the point, and see how it fetched her. She was sitting up for me. I said at once “Ha! ha! Capital riddle for you, my dear. ‘When is a mouse if it spins?’ Because—‘The higher it gets the fewer,’ Ha! ha ! ha!” She looked at me steadily, and I felt myself quailing beneath her gaze; she didn’t laugh a single laugh. “Charles,” she said, “didn’t you once tell me your uncle died in a madhouse!” “Yes,” I replied, “he did. Where are you going?” “Back to dear mother,” she said as she slipped out of the door, never more to enter it. I didn’t try to stop her. I resolved to sit up and understand that riddle or burst. Far into the night I kept on at it, repeating that gruesome question and that weird reply. At length I sallied out into the calm night. I had remembered the sweet refrain of a hymn my mother taught me when a child—“Ask a policeman.” I would; I saw one. I said “Ha! ha! When is a mouse, &c. Ha! ha! ha! Whey [sic] the deuce don’t you laugh?” He struck me on the head, and I fell into the gutter, murmuring, “When is a mouse if it gets higher, because the fewer it gets it spins.” Somebody dragged me to a doctor, and I said at once, “When is a spins if he gets fewer because the mouse it gets the higher?” I heard the doctor say he was quite willing to sign the certificate. I had been standing before a bald-headed J.P., and demanded, “Because is a gets if its mouse when a fewer it hires the spinners, ah! ah! ah!” He signed at once, and they brought me to Winson Green. I know I am mad, but there is no reason why they should ask me, “When is a mouse if it spins?”

On the 2nd of February 1893, the Dorking Advertiser (Dorking, Surrey, England) presented a peculiar phrase that caught my attention: “as when is a mouse if it spins?” This occurrence stands as the second-earliest instance I have come across.

Entertainment.—The Y.M.C.A. provided a thorough change in the way of entertainment on Wednesday evening. The major part consisted of a series of recitals by that popular elocutionist, Mr. Granville Jaggs. […] The conundrum “When is a mouse if it spins?” by its irresistably [sic] comic delivery drew roars of laughter from all.

In the pages of Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (London, England) from Saturday 4th March 1893, we come across the intriguing phrase “why is a mouse when it spins?” Accompanied by the enigmatic response “the higher the fewer”.

New riddle by Mr. McGooseley, after an unusually heavy week: Q. Why is a mouse when it spins? A. The higher the fewer—hic! The Mac—hic!—says he’s got many more quite as original.

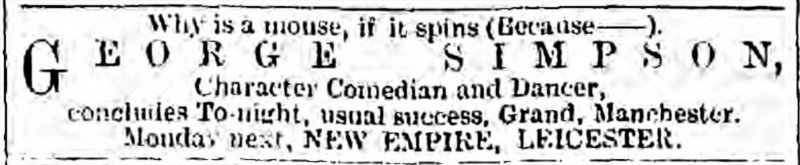

In the captivating advertisement published on Saturday 16th December 1893 in The Era (London, England), the intriguing question arises – why does a mouse spin?

Why is a mouse, if it spins (Because——).

GEORGE SIMPSON,

Character Comedian and Dancer,

concludes To-night, usual success, Grand, Manchester.

Monday next, NEW EMPIRE, LEICESTER.

The excerpt below is from Notes on News, which was published in The Yorkshire Evening Post (Leeds, Yorkshire, England) on Saturday, April 28, 1894.

It would be interesting to know the exact state of mind left in the mind of a man ignorant of the game of golf, after reading the description of the final ties for the Amateur Championship at Hoylake. For the phraseology of the “Royal and ancient game” is more bewildering than that of the Prize Ring, or the football field. Why should it be that “playing to the first hole Mr. Laidlay topped his drive”? It conveys no more meaning to the average man than the statement that “Mr. Ball missed his put to halve,” which very much reminds one, in its apparent meaninglessness, of the old conundrum “Why is a mouse when it spins?” to which the answer is “The higher the fewer.” Golf is a greater puzzle than that.

The excerpt that follows is extracted from The Post Bag, a publication featured in the South Wales Daily Post (Swansea, Glamorgan, Wales) on the memorable Tuesday of July 31st, 1894.

A well-known inn, not far from Goat-street, is just now agitated over the abstruse question: Why is a mouse when it spins? And over the still more abstruse answer: Because the higher the further! This reminds us of the recent conundrum: Why is a fly when it’s a wall? And the mystic response: Because—may God save Ireland!

Nha Trang Institute of Oceanography serves as a fascinating attraction for individuals of varying ages.

On a sunny Sunday, the Salt Lake Tribune of Salt Lake City, Utah, brought forth a column called Society Events, where I stumbled upon the earliest American-English appearance of the phrase I’ve come across. This delightful discovery dates back to the 23rd of July in the year 1893.

Mr. Will Smedley has invented a new puzzle, which he has had patented, and an Eastern firm declares it is great.

It is called “Columbus Discovering America,” and a most intricate affair to work out.

Will is a clever boy at these sort [sic] of things and fully expects to reap a few hundred thousand on his latest invention.

As well remembered he is the originator of the now famous “House That Vanderbilt,” 1 “Hand That Westerfelt” 2 and “Why Is a Mouse When It Spins?”

1 Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), an American entrepreneur and philanthropist, accumulated a vast wealth through his ventures in the shipping and railroad industries.

I have not determined whether Westerfelt may refer to a particular individual.

The phrase “why is a mouse when it spins?” Then occurs, together with the answer “the higher the fewer,” in the column “The Bohemian,” published in “The Buffalo Enquirer” (Buffalo, New York) of Thursday 20th September 1894. Output: In the esteemed column “The Bohemian,” featured in “The Buffalo Enquirer” (Buffalo, New York) on Thursday 20th September 1894, the thought-provoking question “why is a mouse when it spins?” Emerges, accompanied by the intriguing response “the higher the fewer.”

Next time you meet John N. Scatcherd ask him “why is a mouse when it spins?” and he will say “the higher the fewer.” To those who do not understand the circumstances this may not be funny, but it is, just the same, and Mr. Scatcherd will either laugh heartily or grow real angry.

The story below was published in The Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah) on Wednesday, April 8th, 1896.

“WHY IS A MOUSE WHEN—?”

Perfidous [sic] Conundrum Sprang Upon a Peaceful Town by an Enemy of Mankind.

Deputy Collector Thomas J. Dunn, of the marine division in the custom house, is a Harlem Democrat.

“He jollies himself along,” says District Leader McAvoy, “towards the millennium, and he jollies everybody on the way—that is a Harlem Democrat, a jollier.”

He lunched at Delmonico’s downtown yesterday with Deputy Haggerty, of the naval office.

“Now, we’ll have a little fun,” said Mr. Dunn to Mr. Haggerty. “I’ve got a new conundrum. Here it is: ‘Why is a mouse when it spins?’ You see, it is a fool thing and I don’t want you to go crazy—you must be my confederate. We’ll work it up together. The answer is: ‘Because the higher the fewer!’ Just laugh and pretend you see it when I spring it. Sh! here comes Gourley.”

Special Deputy Naval Officer Harrison W. Gourley, silk-hatted and solemn, entered. Gourley has spent thirty years solving customs enigmas. He has a way of interpreting the most puzzling grammatical problems ever incorporated in a tariff bill by a house ways and means committee.

“Come over, Gourley,” said Dunn, “I’ve got a new conundrum for you. ‘Why is a mouse when it spins?’”

“Why, because—why—he—let’s see—why is a mouse—why, darn it! it don’t make sense.”

“Of course it does,” said Haggerty.

“Well, I give it up,” said the special deputy naval officer in disgust.

“Because the higher the fewer,” said Dunn, without a semblance of a smile.

“Because the—what?—oh, hang it all!” and seizing his hat Mr. Gourley fled lunchless.

Then Superintendent Edward Powers of the cotton exchange came in for lunch.

Thus the maddening conundrum spread to the cotton exchange, where within an hour it had half the brokers stark mad. Somebody told it to Assistant Superintendent Beall of the produce exchange, and it got into the wheat pit. Business was suspended, and the brokers hunted chairs, and with pencil and paper wrote and wondered.

Thence it spread to the stock exchange, where, long after the markets closed, solemn-faced men paced the floor, repeating it to themselves.

It is said that when Russell Sage went up to the free lunch in the directors’ room of the Western Union, he ordered “A mouse when it spins, with a little of the higher the fewer.”

Meanwhile Special Deputy Gourley and Chief Clerk Andrew locked themselves in the naval office and struggled with the problem.

It was after 5 o’clock when Mr. Gourley was seen to rush out of his office and strike a bee line for Collector Kilbreth’s office. Breathless, he descended upon the collector.

“Mr. Collector, do you see any sense in this? ‘Why is a’”——

“Mouse when it spins?” gasped the collector, looking up from a pile of papers.

“See here, Gourley, I have troubles of my own. Why is a mou—because—because it—becausue [sic] the fewer—the higher be”——

And again Gourley fled. At the door of the rotunda he met Law Officer Phelps.

“Say, Gourley,” cried Colonel Phelps, “you’re good at conundrums. Why is a——”

But Mr. Gourley had disappeared.—New York World.

The dismissive utilization of why is a mouse when it rotates?

In the wee hours of the morning, have you ever wondered why a mouse twirling around became a symbol of disregard? The subsequent passage hails from the esteemed Table Talk column, featured in The Buffalo Commercial (Buffalo, New York) on the memorable date of Saturday, November 14th, 1896:

“I have myself,” says Mr. G. Bernard Shaw 3 in the Roycroft edition deluxe of that author’s works, “tried the experiment of not eating meat or drinking tea, coffee or spirits for more than a dozen years past, without, as far as I can discover, placing myself at more than my natural disadvantage relatively to those colleagues of mine who patronise the slaughter house and the distillery—but then I go to church.” Well? Why is a mouse when it spins?

3 George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) was an Irish dramatist, reviewer, debater, and political campaigner.

Similarly, the renowned American writer John Dos Passos (1896-1970) employed this expression to casually disregard the literary contributions of both Alfred Tennyson and John Ruskin. This disdainful sentiment was conveyed through a letter addressed to his companion, Walter Rumsey Marvin, while he resided in Paris during the vibrant month of June in 1919. This correspondence, later published in The Fourteenth Chronicle: Letters and Diaries of John Dos Passos (Boston: Gambit Incorporated, 1973), meticulously edited by Townsend Ludington, captured Dos Passos’ candid opinions.

I’m in a horrid mood today—and I feel like lecturing so you are getting the brunt of it—But Rummy my love, I hope you read something else in Freshman English than Shakespeare 6 Ruskin Carlyle 7 and Tennyson—Carlyle I’ll admit as a good old brute of a minor prophet, and of course Shakespeare is enough to counteract all ills—but why in Gods [sic] name Tennyson and Ruskin?—Why is a mouse when it spins?

Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892), the renowned English poet, was a literary figure of great significance.

John Ruskin (1819-1900), a British art and social commentator, was an intriguing figure.

William Shakespeare, born in 1564 and passed away in 1616, was a renowned English poet and playwright.

Thomas Carlyle, a Scottish historian and political philosopher, was born in 1795 and passed away in 1881.

RATIONALISATION ATTEMPTS.

From times of yore, a handful of individuals, abandoning their logical faculties, have concocted elaborate explanations to unravel the enigma of why a mouse spins. Their theories claim that the fewer the height, the more prevalent this phenomenon becomes. The subsequent excerpt is extracted from the captivating column Stories of the Town, featured in the esteemed St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, Missouri) on the memorable Tuesday of December 6th, 1898.

HE KNEW—A company at the City Hall were amusing themselves at the expense of a man who never had heard the gag: “Why is a mouse when it spins.”

The men who knew the joke laughed immoderately each time the senseless question and its senseless answer, “The higher the fewer,” were repeated. The unhappy victim scratched his head and pondered, but couldn’t produce even so much as a smile.

The fun palled on the company and the victim escaped. About two hours later he sought out one of the jokers and with solemn manner thus addressed him:

“I have it. You put that riddle wrong. It shouldn’t be, ‘Why is a mouse when it spins?’ It should be, ‘What is a mouse when it spins?’ Then the answer. ‘The higher the fewer’ is correct, because the faster the mouse spins the higher it goes. Fewer in this case has the meaning of less. That is, the higher it spins the less, or the fewer, you see of it.”

He smiled triumphantly as he finished, and nobody had the heart to enlighten him.

Much more recently, on Monday 18th February 1991, in its column Notes & Queries, The Guardian (London and Manchester, England) published this explanation of why is a mouse when it spins?, Given by one Patrick Nethercot, writing from Durham, in northern England:.Output: In a much more recent occurrence, precisely on Monday 18th February 1991, The Guardian (London and Manchester, England) released a captivating statement in their column Notes & Queries. This intriguing explanation of why a mouse spins was presented by the brilliant Patrick Nethercot, who penned his thoughts from the enchanting city of Durham, nestled in the northern region of England.

This peculiar saying relates to a certain type of governor on steam engines, whereby revolutions of the engine are reduced if a spinning weight (mouse) is lifted up a shaft by its centrifugal force, releasing steam pressure and ensuring fewer revs: the higher, the fewer.

Such systems were common on static engines like those found originally in cotton mills in the heyday of the steam revolution.